The U.S. May Have Just Scored A Win Against China In The Battle Over A Key Mineral

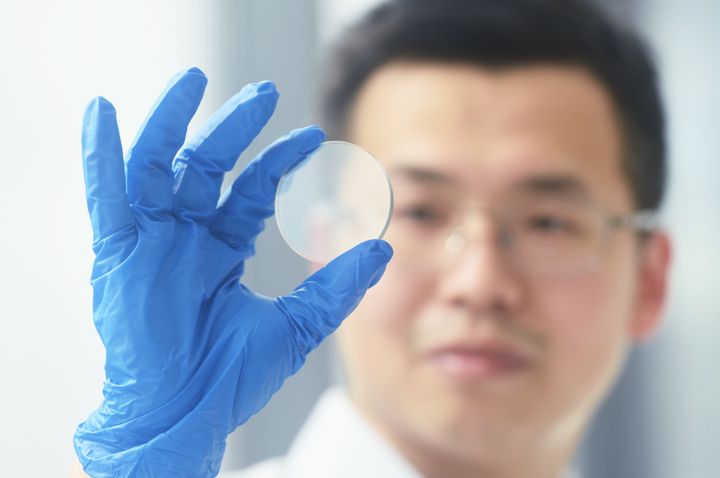

China controls 98% of the world’s production of gallium, a soft, silvery metal used to make semiconductors, LED screens, and solar panels — and a key ingredient in next-generation weapons. Last July, after the United States restricted sales of advanced microchips to the People’s Republic, Beijing responded by slapping export controls on gallium and other minerals used in tech.

While China’s gallium exports plummeted, prices did not immediately surge. Manufacturers across the U.S., Europe and Japan initially brushed off concerns over future supplies, in part because relatively small volumes of gallium are needed for most industrial uses. By last month, however, the cost per kilo of gallium stored in a Dutch depot was going for nearly twice the rate of the stuff warehoused in China, according to data from the market-research firm Fastmarkets.

Advertisement

Beijing appears to be specifically trying to prevent U.S. military suppliers from securing the gallium Washington would need for weapons to defend Taiwan from Chinese invasion — like the American-made Patriot missile launchers whose targeting systems rely on semiconductors made with gallium.

The U.S. hasn’t produced its own gallium in years. That could soon change.

On Thursday, the Salt Lake City-based mining company U.S. Critical Materials Corp. plans to announce the discovery of a large high-grade deposit buried in a remote corner of the Bitterroot National Forest in southwestern Montana, HuffPost has learned.

Gallium is not particularly rare. But China drove much of the world’s other producers out of business over the past decade, as Beijing subsidized its domestic aluminum smelters to churn out gallium as a byproduct. Extracting gallium from underground deposits can be tricky and polluting, too, since the metal is typically dispersed with lots of other minerals, some of which are toxic.

But U.S. Critical Materials said it’s working with the Idaho National Laboratory on a novel method to siphon gallium out of the ore with a minimal environmental footprint. The company said it could turn a profit extracting trace amounts of gallium from ore where the metal made up 50 parts per million tiny bits in the rock. The deposit in Montana, named the Sheep Creek project, contains gallium at as much as 27 times that concentration.

Advertisement

“It’s a geological unicorn,” Harvey Kaye, the company’s executive director, said on a Zoom call with two other top executives Wednesday afternoon.

“Conservatively, that’s billions of dollars,” said Jim Hedrick, a 29-year veteran of the U.S. Geological Survey who now serves as the company’s president.

NurPhoto via Getty Images

From helicopters and by foot, the company’s prospectors analyzed 800 of the 6,700 acres the firm’s owners initially staked more than three decades ago. At first, the company was searching for thorium, a radioactive metal once sought after for atomic weapons. Years later, the firm switched its focus to rare earth metals, the family of elements used to make batteries and other modern technology, which are similarly monopolized by the Chinese government.

While exploring old mineshafts dug decades ago, the company discovered deposits of gallium, which aerial surveys later confirmed ran over a large area.

Advertisement

“This sounds like it’s very good news, in terms of where the U.S. is situated,” said Matthew Funaiole, who’s researched China’s control of the gallium supply chain as a fellow with the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Kaye said U.S. Critical Materials has brought on $3 million in investments over the past two years, and is in the middle of raising more money now.

“We are being very discriminating in terms of where we take money from,” he said. “We’re being offered money from various countries and parts of the world, and we’re not accepting because of national security concerns.”

The firm has enough cash on hand, he said, to manage two years’ worth of development on the mine.

“This company intends to make itself the prime domestic supplier of gallium by virtue of the richness of the deposits, the economics of that deposit and the ability to process it environmentally,” Kaye said.

The firm is also looking to mine, process and sell different kinds of rare earth minerals from the same area, such as niobium, which is used to make alloys such as stainless steel. Brazil is the world’s largest supplier of niobium, but Chinese companies spent billions of dollars over the past decade buying up double-digit percentage stakes in the Brazilian mines.

Advertisement

But China doesn’t “own any of this,” Kaye said. “We’re independent.”

DANIEL MIHAILESCU via Getty Images

The tracts U.S. Critical Materials controls are located at least 40 miles from any town, and do not intersect with any tribal lands, the firm said.

But the company’s push to develop its claims in the area has already drawn fierce opposition from local and national conservation groups. In a letter last month to the U.S. Forest Service, Friends of the Bitterroot and other environmental organizations warned that mining operations could jeopardize several threatened species, including grizzly bears, wolverines, Canada lynx and bull trout. They also voiced concern about what a mine could mean for water quality and the local economy. The exploratory project sits near the headwaters of the Bitterroot River, a renowned trout fishery and one of the most popular angling destinations in the state.

“Just the thought of an industrial scale mine on the Bitterroot River horrifies most Bitterrooters,” Larry Campbell, conservation director for Friends of the Bitterroot, said in a statement accompanying the organization’s letter. “A worse location would be hard to find.”

The mining industry has a long history in Montana — and a long legacy of pollution. The city of Butte, once known as “the richest hill on earth” and ruled by three industrialists dubbed the “Copper Kings,” is now home to the Berkeley Pit, a gaping former open pit copper mine that is full of water laced with toxic chemicals and heavy metals.

Advertisement

Last month, the Montana Supreme Court overturned a lower court’s ruling and cleared the way for a controversial underground copper mine, called Black Butte, to move forward. If constructed, it would be the first new copper mine to open in Montana in more than four decades.

While the U.S. still produces large amounts of certain metals, mining as an industry largely shifted overseas in the latter half of the 20th century, as producers sought out laxer environmental regulations and cheaper labor. Where the U.S. was once the top supplier of rare earths, China now controls 90% or more of the market.

Beijing’s dominance over the minerals needed for batteries, wind turbines and solar panels is frequently cited as a reason to slow the transition away from fossil fuels, lest the U.S. cede too much power over its energy systems to its rival.

“This company intends to make itself the prime domestic supplier of gallium by virtue of the richness of the deposits, the economics of that deposit and the ability to process it environmentally.”

– Harvey Kaye, U.S. Critical Materials Corp. executive director

Scarred by the early 1970s Arab oil embargo that saw the world’s top oil producers cut off energy supplies over the West’s support for Israel, U.S. policymakers long focused on the availability of domestic supplies of fossil fuels.

Advertisement

It wasn’t until 2010, when China briefly halted shipments of rare earths to Japan amid a spat over uninhabited islands both nations claim, that concern over Beijing’s virtual monopoly on key minerals began to grow. Beijing now claims its restrictions on exporting gallium, germanium and graphite are for national security reasons.

Mark Squillace, a professor of natural resources law at the University of Colorado, Boulder, told HuffPost called U.S. Critical Materials’ discovery “interesting,” but said it’s too early to say where the project will go.

“It seems like a promising deposit for the company, and a fairly significant deposit,” he said. “What I don’t know is if it’s a practical thing to develop in the location where it’s at. I don’t know what kind of opposition is going to form.”

Squillace noted that neighboring Canada and other U.S. allies are pursuing operations to process rare earth minerals to combat China’s dominance.

“They need to know there are multiple places, particularly friendly places, that are going to be producing and processing these materials,” he said.

Advertisement

“We shouldn’t just have other countries producing minerals that we’re using,” he added. “But obviously there are ways to do it better than other ways. … Particularly in Montana, with the problems that have come up with some of the existing mining, I suspect this is going to get a lot of pretty close scrutiny.”

If U.S. Critical Materials’ project pans out, Funaiole said the gallium it produces will likely serve as a key domestic supply for military contractors, and could even end up being exported to U.S. allies if generated in large enough quantities. But Funaiole said Washington should be more proactive in seeking out new domestic sources of metals.

“It’s a good first step,” he said. “But this shouldn’t be something where people pat themselves on the back for too long, because there’s a whole lot more critical minerals we need to think about besides gallium.”

Comments are closed.