‘I Was Just Waiting To Die’: Survivors Correct The Record On Jonestown Massacre

On a remote airstrip in the South American country of Guyana, Jackie Speier lay gravely wounded behind the wheel of a small plane. The 28-year-old legal adviser to a California congressman had been shot five times. Near her lay the bullet-riddled bodies of her boss, Rep. Leo Ryan, three journalists and a woman fleeing a cult commune known as Jonestown.

When help finally came, Speier and other survivors learned the almost incomprehensible truth about what they had left behind. Six miles away, more than 900 bodies lay decomposing in the heat. One third of them were children. They were surrounded by syringes and toppled paper cups containing poison-laced punch.

Advertisement

According to a massive research project sponsored by San Diego State University, 918 people died on Nov. 18, 1978, in what came to be known as the Jonestown Massacre, the subject of the riveting new docuseries, “Cult Massacre: One Day in Jonestown.”

Bettmann via Getty Images

The three-part series, which premiered Monday on Hulu (and will air on National Geographic on Aug. 14), is deeply unsettling. It stands out from other documentaries about Peoples Temple cult leader Jim Jones by disputing the all-too-pervasive narrative that the victims were complicit in their deaths and by providing important context for the massacre. Modern-day interviews — including survivors like Speier, members of the Peoples Temple who escaped, U.S. military personnel tasked with counting and removing the bodies, and Jim Jones’ son himself — contextualize the harrowing video, photos and audio, much of it previously unaired.

Even Speier, who years later was elected to Ryan’s former seat in Congress, had not seen some of the footage before she watched the docuseries.

Advertisement

“It was almost like an out-of-body experience — like it happened to someone else, and I was just watching this horrific saga,” she told HuffPost. “And I sit back and [think], ‘God, did this really happen to me?’

“Unfortunately, it really did.”

California Historical Society

The Peoples Temple

Rev. Jim Jones founded the Peoples Temple in Indianapolis in the 1950s, preaching the concept of what he called “apostolic socialism.”

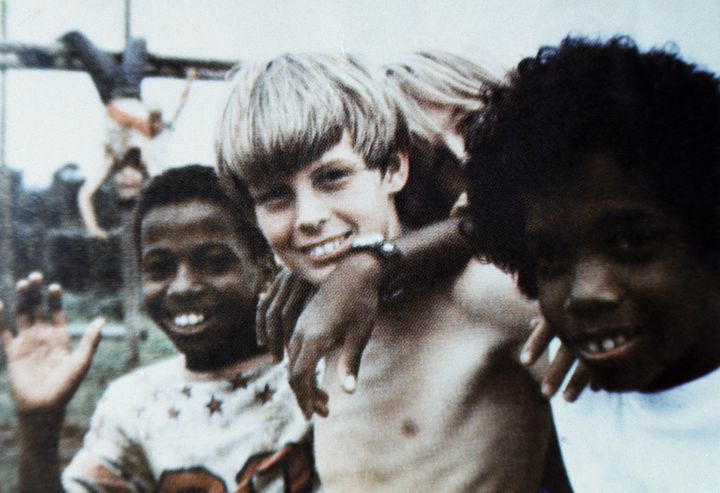

Jones and his followers advocated for the redistribution of wealth, free social services and racial harmony. Although Jones was white, the majority of the members of the Peoples Temple, which relocated to San Francisco in the 1970s, were Black.

Despite the church’s outward appearance of racial unity and equality — in one shot in “Cult Massacre,” a “Black Is Beautiful” sign is seen in Jonestown posted above cheerful drawings from children — it was clear to observers that Black members lacked agency in the group.

Advertisement

“Most of those in power were white, and most of the African American population were not,” Speier said about the structure of the Peoples Temple.

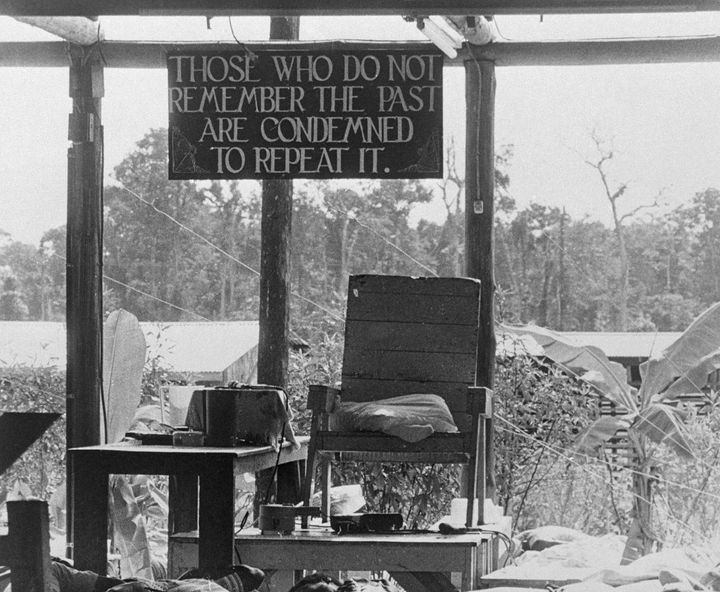

Under Jones’ direction, church members toiled to build Jonestown — officially called the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project — from the ground up on 3,800 acres of land Jones leased in the isolated jungle. People who were lured to Guyana with the promise of being “happy and untethered” from the U.S. government instead found themselves in what survivors described as a prison camp.

Whether church members were happy to be in Jonestown or not, they were unquestionably prisoners of Jones. The self-proclaimed messiah was a cruel tyrant who confiscated his followers’ passports and money in Guyana, prevented them from communicating with their loved ones back home and punished those who questioned his authority. People were prevented from leaving by armed guards and the treacherous jungle terrain surrounding their commune.

Jones even deprived them of food, which Speier realized when the delegation was having breakfast in the commune the morning of the massacre.

She said she is still haunted by the face of a Black woman in her late 80s who Speier saw “stuffing bacon into her dress pocket.”

Advertisement

“And it made me realize that it was all for show — that the food they were normally providing them was much less than what they were receiving that day. Her face still pops into my head from time to time,” Speier said.

AP Photo/Ray Stubblebine

Concerned Relatives

Congressman Ryan’s fact-finding delegation was a response to allegations of abuse at Jonestown by a group called Concerned Relatives, who said they were “bewildered and frightened” about what Jones was doing to their families.

“Their human rights are being violated and the fabric of our family life is being torn apart,” they wrote in a 1970s flyer that they hoped would attract the attention of politicians and the public. The group warned that Jones was conducting mass suicide drills — he called them Operation White Knight — “to condition his members to die for ‘the cause’ at the moment he gives the order.”

Their pleas spurred Ryan, who counted the relatives and members of the cult at Jonestown among his constituents, to investigate their concerns firsthand. He flew to Guyana with Speier as well as some People Temple defectors, family members and a team of journalists.

Advertisement

Much of the footage of their visit was captured by NBC cameraman Bob Brown and San Francisco Examiner photographer Greg Robinson. Both of them were fatally shot in the ambush on the Port Kaituma airstrip, as was NBC correspondent Don Harris.

“I was expecting to die,” Speier said. “I was just waiting to die.”

The fifth person killed at Port Kaituma was Patricia Parks, a member of the Peoples Temple who was trying to escape that day. She was shot in the head while sitting inside the plane she hoped would carry her to safety.

AP Photo/San Francisco Examiner/Greg Robinson)

The delegation

When the fact-finders were allowed to visit Jonestown, the followers’ smiles, enthusiasm and praise of their leader at first seemed to persuade Ryan that all was well.

“Whatever the comments are, there are some people here who believe this is the best thing that ever happened in their whole life,” he said onstage in a pavilion to rousing cheers and applause from Jones’ followers.

Advertisement

But then people started slipping secret notes to members of the delegation, saying they wanted to leave — “confirmation,” Speier said, “that people were being held there without their will.”

Speier did meet individually with church members who insisted they wanted to stay in Jonestown, but she had trouble believing them.

It seemed like they had “memorized a script,” she said. “They basically all said the same thing: ‘I love it here. I have no interest in reconnecting with my family.’”

The tension in the air as word spread about the defectors was palpable.

In film footage shown in “Cult Massacre,” Jones’ increasing agitation is evident. His jaw is clenched while beads of sweat form on his reddening face. He repeatedly licks his lips and whispers urgently to his guards.

Then someone in the pavilion tried to stab Ryan. Others intervened and he wasn’t injured, but the delegation knew they were in peril. Jones said any followers who wanted to join them were free to leave — but then sent his armed guards to ambush them on the runway.

Advertisement

Bettmann via Getty Images

The massacre

Meanwhile, Jones was ordering his followers to poison themselves and their children.

“Fail to follow my advice, you’ll be sorry. You’ll be sorry,” he tells his congregation in audio that was recorded on the scene.

“Die with a degree of dignity, lay down your life with dignity,” Jones said. “Don’t lay down with tears and agony.”

But Jones’ followers’ deaths were agonizing. Meanwhile, he died from a gunshot wound. Whether it was self-inflicted or not is still debated, but it wasn’t painful.

Speier struggled to describe the sounds in the audio clip as Jones’ followers responded to his instructions, some of them asking why the children had to die too.

Advertisement

“It was just this hopeless — I don’t know what the word is. Cry, I guess. A hopeless cry, but they just became resolved … there’s a herd instinct going on.”

That, and the threat of guards standing around with guns if they didn’t do what they were told.

So they drank. It was a mixture of cyanide and grape Flavor-Aid, which was reported at the time as Kool-Aid. “Drink the Kool-Aid” became a catchphrase for blindly following authority.

The phrase still infuriates Jones’ son Stephen, who opens up about his conflicted relationship with his father in “Cult Massacre.”

“It so dehumanizes the people who died there, and it’s so off the mark,” Jones says in the series.

“That night was murder.”

For decades, what happened at Jonestown was described as mass suicide, a notion that “Cult Massacre” convincingly discredits.

“From very early on, I would bristle when people said mass suicide,” Speier said, pointing out that people were injecting cyanide into infants and children.

Advertisement

“They had gunmen standing at all of the edges of the pavilion. And they had lost control over their own minds,” she said.

A member of the U.S. Special Forces who was sent to Jonestown after the massacre said he found people with syringes stuck in the back of their necks, and evidence that others had been held down and forced to drink the poison.

The dead were vastly undercounted at first — initial reports had the death toll at 300 — and officials later found children “tucked underneath” the adults, the Special Forces member said on “Cult Massacre.”

Jones preyed on vulnerable people, a man who left Peoples Temple says on “Cult Massacre.”

“They have been victims of racism, victims of poverty. Then Jones came along and offered them something. They trusted him and they believed him. They thought they were changing the world or at least they thought they were changing their lives. But he was a crazy son of a bitch. And he was willing to see them all die. I don’t know why he needed to destroy these people.”

The people who died at Jonestown were the subject of ridicule and contempt for decades. Outsiders simply didn’t understand the torment Jones’ followers endured, Speier said.

Advertisement

“Those who weren’t caught up in Jim Jones’s lies and the emotional stranglehold he had on people have no way of being able to appreciate how difficult it was for them,” Speier said.

Bettmann via Getty Images

Comments are closed.