I Randomly Decided To Pay Off A School’s Lunch Debt. Then Something Incredible Happened.

The thing about witnessing a 7-year-old having their hot lunch tray yanked away and replaced with a cold sandwich — what cafeteria workers in the biz euphemistically call an “alternative meal” — is not just the obvious cruelty of the public spectacle, though there’s plenty of that.

It’s the bizarre normalization of the whole affair, as if we’ve collectively agreed that fiscal responsibility is best taught through the ritual humiliation of second graders. It’s watching the adults in the room — ordinary, decent people who’d never dream of snatching food from a child in any other context — perform this strange ceremony with the mechanical resignation of DMV employees, while around them life continues uninterrupted, because this is just How Things Are.

I never actually witnessed this scene myself, but I’ve interviewed enough lunch ladies, principals and kids to construct a sort of composite mental image that now plays on an endless loop between my ears. It’s become my own personal film of educational injustice, frame by frame, in high-definition slow motion: the momentary confusion on the child’s face, the hushed explanation from the cashier, the sudden understanding dawning in the kid’s eyes, the burning shame that follows.

Advertisement

It’s the kind of thing most adults have trained themselves not to see, which is how I managed to live 29 years without recognizing an entire shadow economy of grade-school debt operating in the fluorescent-lit cafeterias of Utah, where I live. The invisibility of it all seems almost by design — a sleight-of-hand that kept this particular form of childhood poverty comfortably out of my peripheral vision until an algorithm decided I needed to know about it.

I was doomscrolling through news articles one evening — this was June 2024, which feels simultaneously like yesterday and several epochs ago — when I saw a headline stating there was $2.8 million in school lunch debt across Utah.

Advertisement

That seemed, you know, bad.

But it also triggered that now-familiar mental reflex where I immediately wondered if this was real or just another informational phantom conjured by our collective digital hallucination machine.

Advertisement

So I called my local school district, because that seemed like the sort of practical thing a reasonably civic-minded adult might do. I had no particular plan beyond basic verification. The woman who answered sounded simultaneously surprised and unsurprised that someone would call about this, if that makes sense. Yes, lunch debt was real, she told me. Yes, it affected children in our district. Yes, it was about $88,000 just for elementary schools, just in my district. And then, almost as an afterthought, she mentioned that Bluffdale Elementary — a school I had no personal connection to — had about $835 in outstanding lunch debt.

The figure hit me like one of those rare moments of absolute clarity, utterly devoid of irony or ambiguity. Eight hundred and thirty-five dollars was the cost of preventing dozens of children from experiencing that moment of public shame I couldn’t stop imagining. It was less than some monthly car payments. It was approximately what I had spent the previous month on DoorDash and impulse Amazon purchases. The grotesque disproportion between the trivial financial sum and the profound human consequence felt like a cosmic accounting error.

“Can I just… pay that?” I asked, half expecting to be told about some bureaucratic impossibility.

“Um, sure,” she said. “Let me transfer you.”

Two days later, I drove to the district office during my lunch break from work and handed them a check. The entire process took approximately 11 minutes, during which I felt a disorienting mix of emotions: satisfaction at the immediate resolution, embarrassment at how easy it had been for me, and something more complicated — a dawning awareness of my own complicity in a system I hadn’t bothered to notice until now.

Advertisement

I wish I could tell you that I immediately founded a nonprofit, that I possessed some cinematic moment of purpose where an orchestral score swelled beneath my newfound determination. The truth is considerably less Hollywood-ready. I went back to work, coached my basketball team that evening, made dinner for my daughter, and didn’t think about it again for nearly two weeks.

What brought me back was the number: $2.8 million. It’s such a staggering figure. There’s more to the story than change lost between the couch cushions — families aren’t forgetting $2.8 million in lunch debt. People are suffering.

So, I called another district. Then another. I started a spreadsheet, which is what middle-class professionals do when faced with systemic problems — we quantify things, as if converting human suffering into Excel cells might render it more manageable. I learned that some elementary schools had thousands in debt. I learned that, contrary to popular belief, most school lunch debt doesn’t come from low-income families — those kids generally qualify for federal free lunch programs. It comes from working families who hover just above the eligibility threshold, or from families who qualify but don’t complete the paperwork for various reasons, ranging from language barriers to pride to bureaucratic overwhelm.

Advertisement

I began to realize that the problem is both smaller and larger than I had initially understood. It’s smaller in that the per-school amounts were often relatively modest. It’s larger in that the entire structure of how we feed children at school is a tangle of federal programs, income thresholds, paperwork requirements, and local policies — all of which seemed designed to maximize shame and minimize actual nutrition.

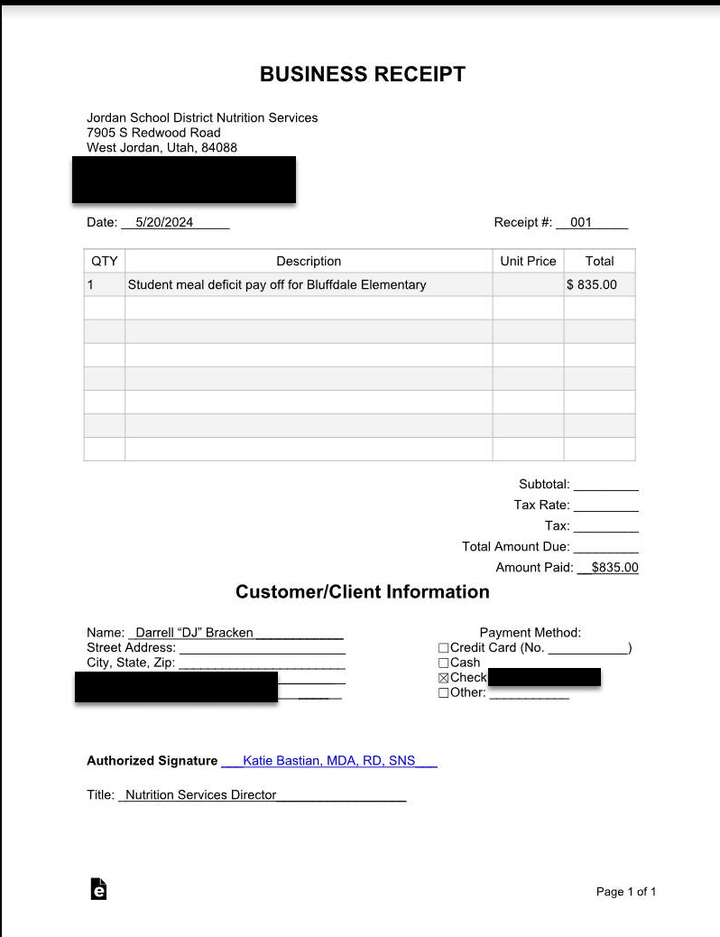

The Utah Lunch Debt Relief Foundation began not with a mission statement or a business plan, but with a post I shared on social media asking people if they would be willing to chip in, along with the receipt I had been given for Bluffdale Elementary’s debt. Within a week, I’d raised $6,000. Within a month, $10,000. The mechanics were almost embarrassingly simple: I would call a school, verify their lunch debt amount, write a check, drop it off, repeat. People seemed to find the concrete nature of it satisfying — this specific school, these specific kids, this specific problem solved.

Courtesy of DJ Bracken

Advertisement

But something strange happens when you start trying to solve a problem that nobody else seems particularly interested in solving. You become, almost by default, something of an expert on the issue. Principals started calling me. Then the reporters. Then, state legislators. I found myself in meetings where people asked what I thought about reduced-price meal thresholds and federal reimbursement rates — subjects about which I had approximately zero expertise beyond what I’d frantically Googled in the parking lot before the meeting.

There’s a peculiar form of impostor syndrome that comes with accidental advocacy. I still remember sitting in a meeting with actual policy analysts and education officials, feeling like a child who had wandered into the wrong classroom, while simultaneously realizing that I somehow knew more about certain aspects of the lunch debt situation than these lifelong professionals did. It wasn’t because I was smarter or more dedicated, but simply because I’d been looking directly at a specific problem they only encountered as part of a much larger institutional landscape.

The most disorienting aspect of this accidental journey has been confronting the philosophical contradictions inherent in what I’m doing. On Monday, I’ll find myself arguing passionately that school lunch should be universal and free, like textbooks or desks — a basic educational supply. On Tuesday, I’ll be raising money to pay off debts in a system I just spent Monday arguing shouldn’t exist at all. The cognitive dissonance is sometimes overwhelming. Am I enabling a broken system by patching its most visible failures? Am I letting policymakers off the hook by providing a band-aid that makes the bleeding less visible?

Advertisement

One particularly sleepless night, I found myself spiraling into what I’ve come to think of as “the advocacy paradox”: If I succeed completely in paying off all lunch debt, will that remove the urgency required to change the system that creates the debt in the first place? But if I don’t pay it off, actual children — not abstractions, but specific kids with specific names who like specific dinosaurs and struggle with specific math problems — will continue to experience real shame and real hunger tomorrow. The perfect threatens to become the enemy of the good, but the good threatens to become the enemy of the fundamental.

I don’t have clean resolutions to these contradictions. What I do have is a growing conviction that the either/or framing is itself part of the problem. We live in a culture increasingly oriented around false dichotomies — around the artificial polarization of complex issues into two opposed camps. You’re either focused on immediate relief or systemic change. You’re either practical or idealistic. You’re either working within the system or fighting against it.

But what if the truth is that we need all of these approaches simultaneously? What if paying off a specific child’s lunch debt today doesn’t preclude advocating for a complete structural overhaul tomorrow? What if the emotional resonance of specific, concrete actions is precisely what builds the coalition necessary for systemic change?

Advertisement

This isn’t just abstract philosophizing. Last year, we helped secure the passage of HB100 in Utah, which makes reduced-price children (those who are low income but don’t qualify for free lunch) eligible for free lunch and prohibits schools from engaging in lunch-shaming practices. The bill wouldn’t have passed without the stories we were able to tell — stories that came directly from our work, paying off debts and talking to families. The incremental work created the conditions for the structural change.

We’ve now raised over $50,000 and eliminated lunch debt at 12 schools. That’s 12 schools where kids don’t get their trays taken away, where a basic human need isn’t transformed into an object lesson about fiscal responsibility, where childhood can proceed with one less vector for shame and stigma.

I still don’t know if we’ll reach our ultimate goal of eliminating all school lunch debt in Utah. The statistical probability seems vanishingly small. The system has tremendous inertia. New debt accrues even as we pay off the old.

Advertisement

Sometimes, in my less optimistic moments, it feels like trying to empty the ocean with a teaspoon.

But here’s the thing about seemingly impossible tasks: they’re only definitively impossible if you don’t attempt them. There’s a curious quantum uncertainty to social change — the act of working toward it alters the probability of its occurrence. Each school we help makes the next one slightly easier. Each conversation changes the parameters of what’s considered normal or acceptable. Even failed attempts leave behind a residue of possibility that wasn’t there before.

I no longer believe the question is whether we’ll eliminate all lunch debt everywhere forever. The question is how many children we can spare from that moment of public shame while simultaneously building the case for a world where that moment isn’t possible at all. The question is whether we’re willing to live with the messy contradictions of simultaneous immediate action and long-term vision. The question is whether we’re willing to do something imperfect now while working toward something better later.

My daughter asked me recently why I spend so many evenings on the phone talking about school lunches. I told her about the kids who get their trays taken away. Her face scrunched up in that particular way that children’s faces do when they encounter an injustice so fundamental it cannot be reconciled with their understanding of how the world should work.

Advertisement

“That’s stupid,” she said with 7-year-old clarity. “Why don’t they just let them eat?”

Why indeed. The answer involves federal policies and budget constraints, as well as the peculiar American mythology surrounding self-reliance, which somehow extends even to second-graders. But there’s a piercing truth in her question that cuts through all the adult rationalization: Why don’t we just let them eat?

It remains the central question of this work. And if enough of us keep asking it — while simultaneously doing what we can in the deeply imperfect present — perhaps one day we’ll live in a world where we don’t need to ask it anymore.

DJ Bracken lives with his 7-year-old daughter Liara and splits his time between coaching basketball and fighting school lunch debt. After personally paying off $835 at a local elementary school, DJ founded the Utah Lunch Debt Relief Foundation, which has raised over $50,000 and paid off the lunch debt of 12 Utah schools. His advocacy helped pass HB100, legislation that changed “reduced-price” lunch kids into “free” lunch kids and prohibited lunch shaming in Utah schools. Follow his work on his Substack, “Lunch Money,” or donate directly to lunch debt relief at www.utldr.org. Contact him at djbracken@utldr.org.

Advertisement

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch at pitch@huffpost.com.

Comments are closed.